At a glance: Monitoring emissions reduction (2024)

A summary of key findings from our 2024 emissions reduction monitoring report.

This page provides a summary of key findings from Monitoring report: Emissions reduction (July 2024), excerpted from the chapter 'At a glance: monitoring emissions reduction.'

For more information, download our full report at the link above, browse supporting documents, or read our media release about this report.

Contents:

- At a glance: monitoring emissions reduction

- What we found

- Summary for decision makers

At a glance: monitoring emissions reduction

He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission (the Commission) is tasked under the Climate Change Response Act 2002 (the Act) with the job of independently monitoring Aotearoa New Zealand’s progress on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Our 2024 report is the first of what will be annual monitoring reports on reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. These objective assessments will build into a series of snapshots forming a picture over time of how the country is tracking towards its climate change goals.

The annual reports will present our assessment of:

- the adequacy of the Government’s current emissions reduction plan and its implementation

- how the country is tracking against the ‘emissions budgets’ that serve as stepping-stones to the long-term target

- progress towards that 2050 emissions target (Figure A1).

The monitoring covers reductions in gross emissions, and removals of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (mostly carbon dioxide absorbed by forests as trees grow), to report against the country’s net emissions target.[i]

Box A1: The questions at the heart of this report

The 2024 report has this overall purpose:

To track progress towards achievement of the first emissions budget (2022–2025), the second budget (2026–2030) and the third budget (2031–2035), and progress towards the 2050 target, and to assess the adequacy of the first emissions reduction plan and progress in its implementation.

We address this through four questions:

- What progress have we seen in emissions reductions to date?

- How is the country tracking towards meeting the first emissions budget for 2022–2025?

- How is the country tracking towards meeting the second emissions budget (2026–2030) and the third emissions budget (2031–2035) and the 2050 target, under current emissions reduction policies and plans?[ii]

- What is needed for Aotearoa New Zealand to be on track for future emissions budgets and the 2050 target?

These are the headings we use for the key findings summarised below and shown in full in Chapter 3: Our key findings.

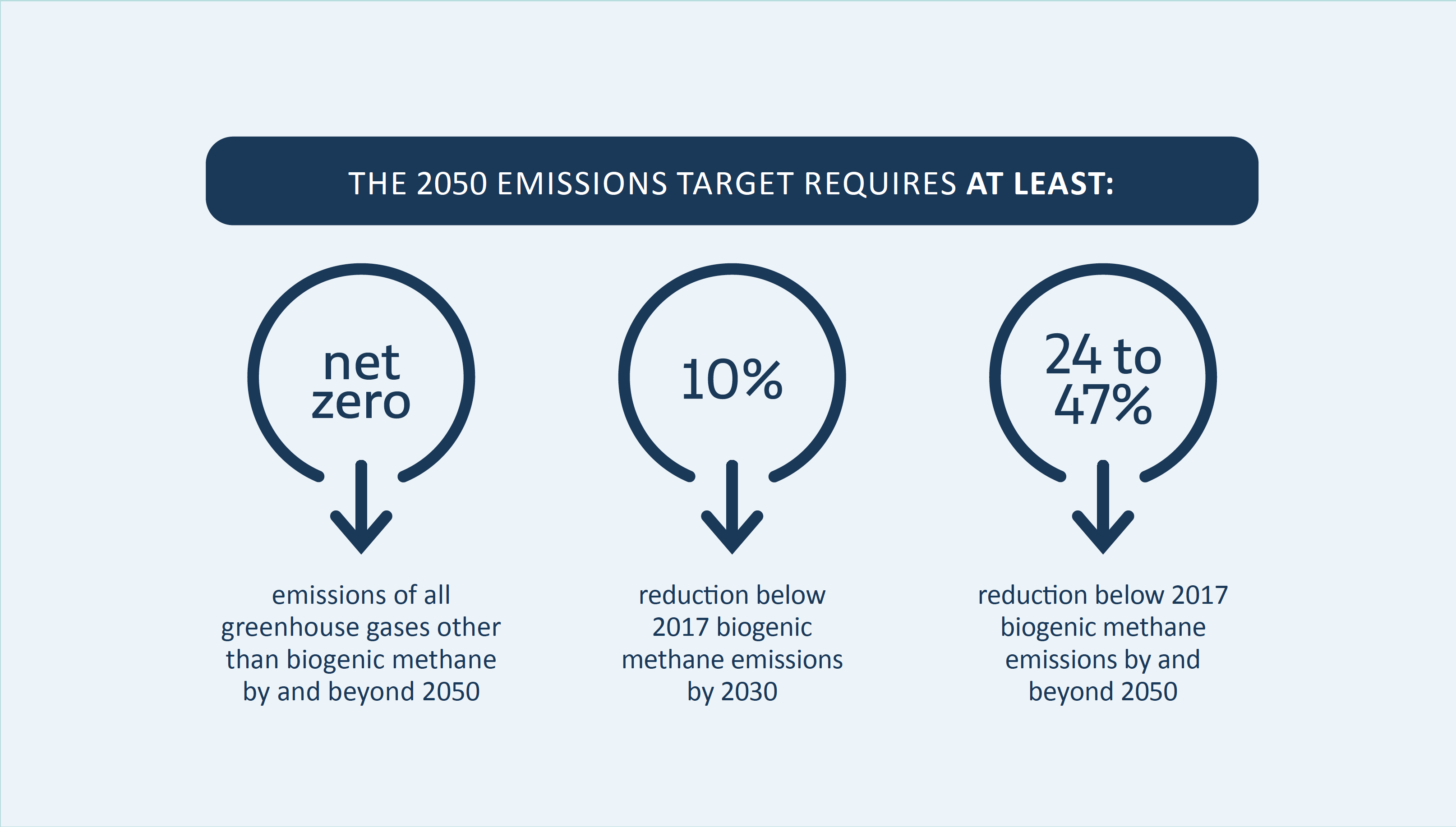

Figure A1: Aotearoa New Zealand’s 2050 emissions target

Source: Commission analysis. Click to view a larger version.

What we found

This summary provides an ‘at-a-glance’ view of the key findings from our assessment, organised under the four fundamental questions it asks (Box A1). Chapter 3 sets out our findings in full, while Part B of this report presents the supporting evidence.

The assessment shows there is an urgent need to strengthen policies and strategies to put Aotearoa New Zealand on track to meet future emissions budgets and the 2050 target, including the 2030 biogenic methane component of the target.

We identify a range of opportunities to work towards the country’s climate goals. This includes a focus on areas where progress has happened faster and more effectively than expected, as these areas offer ways to maintain and enhance momentum.

The assessment of the adequacy of the emissions reduction plan also identifies areas of uncertainty in policy direction and funding, particularly for managing potential impacts of emissions reduction policy, and for the delivery of actions focused on iwi/Māori. These are key challenges that decision-makers will need to address to build a transition to a low emissions Aotearoa New Zealand that supports all to thrive.

The information available for this report

As required in section 5ZK of the Act, our analysis is based on the latest available data from New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory (GHG Inventory), combined with “the latest projections for current and future emissions and removals”.[iii]

The GHG Inventory published in April 2024 provides data up until the end of the 2022 calendar year: the first year of the first emissions budget. As explained in Chapter 2: Our approach, we complement the GHG Inventory data with emissions estimates and projections to provide a more up-to-date picture of progress. Projections have an inherent level of uncertainty associated with them; this is noted within our findings, where relevant.

The GHG Inventory published in 2024 does not include calculations using the target accounting method on net emissions removals by absorption in forests (‘net removals by forest’). This means there are no official estimates for net emissions up to 2022 under the accounting rules that apply to Aotearoa New Zealand’s emissions budgets.[iv] In their absence, we have relied on the most recent government projections for removals by forests under target accounting, published in 2023. This is a key caveat to our findings on how Aotearoa New Zealand is currently tracking towards meeting the first emissions budget.

For more info, see the following sections of the report:

Part A provides an overview and summary, including the report’s purpose and context, the approach taken to this monitoring, and a synthesis of our key findings.

Part B provides the evidence for our findings, including analysis of system-wide areas (Chapters 5–8) and analysis of sectors reported in the GHG Inventory (Chapters 9–12).

Summary for decision makers

Precis of key findings – for the full findings with illustrating figures, see Chapter 3.

Global situation

- Global temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions have reached new highs, but climate action and use of new technologies is slowing the rise of emissions (Chapter 4). The evidence shows there is continuing global progress on emissions reduction, but further efforts are required to reach global goals.

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s gross domestic product (GDP) has risen by 147% since 1990, while gross emissions have only risen by 14% over that time. A global pattern of decreasing gross emissions-per-unit of GDP highlights that a strong and growing economy is possible without increasing gross emissions. While Aotearoa New Zealand’s gross emissions-per-GDP ratio since 2014 has been lower than the global average, it is still the third-highest ratio of all advanced economies, behind only Australia and Canada.[v]

Question 1: What progress have we seen in emissions reductions to date?

- Gross emissions in Aotearoa New Zealand have declined each year since 2019, as a result of government policies combined with the impact of external factors – such as economic conditions, weather conditions, and international fossil fuel prices.

- Gross emissions fell in every sector from 2021 to 2022, with the largest drop coming from energy and industry. Those sectors accounted for nearly three-quarters of the gross emissions reductions in 2022.

- These emissions reductions largely rely on variable factors that could change in any year – for example high rainfall, which supported higher hydroelectricity generation and less power generation from coal and gas. The rate of emissions reductions seen in 2022 is therefore unlikely to continue.

- Progress in reducing net emissions is currently uncertain due to the absence of official data on carbon removals by forests using the accounting approach that applies to Aotearoa New Zealand’s emissions budgets and targets (‘target accounting’). Based on government projections of carbon removals under target accounting published in 2023, net emissions have also fallen since 2019.

Question 2: How is the country tracking towards meeting the first emissions budget for 2022–2025?

- Available emissions data and projections are consistent with the first emissions budget being met. However, this estimate has high uncertainty due to risk factors such as increased levels of loss of forest area (deforestation), low rainfall (dry years) for hydroelectricity generation, and rising transport emissions. Further action by the Government to reduce emissions would decrease the risk of missing the first emissions budget.

- There is opportunity to increase momentum by focusing on areas where there have been positive signs of change, such as uptake of low and zero emissions vehicles. While there is now limited time in the first emissions budget period for new policies to have much impact, increased effort on measures that have proven effective could improve chances of meeting the first emissions budget. Those reductions would also build over time to contribute to meeting the second emissions budget (2026–2030) and third emissions budget (2031–2035).

Question 3: How is the country tracking towards meeting the second emissions budget (2026–2030) and the third emissions budget (2031–2035) and the 2050 target, under current emissions reduction policies and plans?

- There are significant risks to meeting the second and third emissions budgets and the 2030 biogenic methane target.

- The agriculture and transport sectors show the largest risks, and insufficient action to reduce emissions in these sectors will put the second and third emissions budgets at risk.

- If there are insufficient reductions in gross emissions for the second emissions budget (2026–2030), this cannot be made up by increased removals of carbon dioxide through forestry. Additional forest planting can no longer make much difference to this period, because the rates of increase of carbon removal through trees is slow in the early stages of new plantings.

- The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) is an essential part of an effective policy package for reducing emissions, but it cannot itself ensure the emissions budgets are met. The way the scheme operates does not provide certainty about the units available to emitters over the period to 2035. It therefore does not provide certainty about the quantity of emissions from the sectors and sources it covers.

Question 4: What is needed for Aotearoa New Zealand to be on track for future emissions budgets and the 2050 target?

- A well-designed policy package is needed to deliver cost-effective and durable climate action that will achieve the country’s emissions budgets and 2050 target.

- Actions to meet climate goals can have positive impacts, such as reducing living costs, but there can also be negative impacts. The way those impacts fall on different sectors, regions, and communities, and across generations, needs to be managed to avoid inequities.

- There is currently a lack of clarity in how the Government plans to manage potential impacts of emissions reduction policy and to grasp opportunities to improve the lives of New Zealanders, particularly for those most affected by emissions reduction policies.

- The effectiveness of emissions pricing policies (such as the NZ ETS) is limited by barriers such as access to capital, and other challenges in systems, infrastructure and incentives that make it difficult for people and businesses to choose options that have lower emissions. Policies targeted to address these barriers could unlock cost-effective action and make the NZ ETS more effective.

- New policy measures in agriculture will be needed alongside continued action on waste emissions to meet the 2030 biogenic methane component of the long-term target. This 2030 goal applies specifically to reductions in biogenic methane and can only be achieved through action in the agriculture and waste sectors; the goal limits flexibility in how the second emissions budget (for 2026–2030) can be achieved.

- In addition to action on critical sectors, our assessment identified opportunities for government action on issues that limit emissions reduction across the economy. An example would be to ensure robust supply chains and availability of a skilled workforce to increase the speed that the energy sector can deliver projects to reduce emissions. This is particularly important, given that reliable and affordable electricity supply is critical for reducing emissions from transport, industries and buildings, and has flow-on effects across the economy.

- As noted for the current emissions budget period, there are opportunities for more ambition in some areas of emissions reduction where progress has been faster than expected. Examples include faster than anticipated uptake of low and zero emissions vehicles, further emissions reductions from industry, and reducing geothermal emissions through gas capture and reinjection. Maintaining and building momentum in these areas could help balance risks of underachievement in others.

Footnotes

[i] There are also end-of-budget reports required in the Act, which will evaluate progress made in a particular budget period. The first of these is due in 2027, for the first emissions budget (2022–2025).

[ii] See Chapter 2: Our approach for what we have considered alongside the plan, which includes evolution in policy since the emissions reduction plan was published, up to 1 April 2024.

[iii] Climate Change Response Act 2002, section 5ZK(2)(a).

[iv] Official estimates of net emissions under target accounting will be published in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Biennial Transparency Reports under the Paris Agreement, the first of which is due by 31 December 2024. Those official estimates will also be reported annually in the GHG Inventory from 2025.

[v] See Chapter 4, Box 4.2 for further information